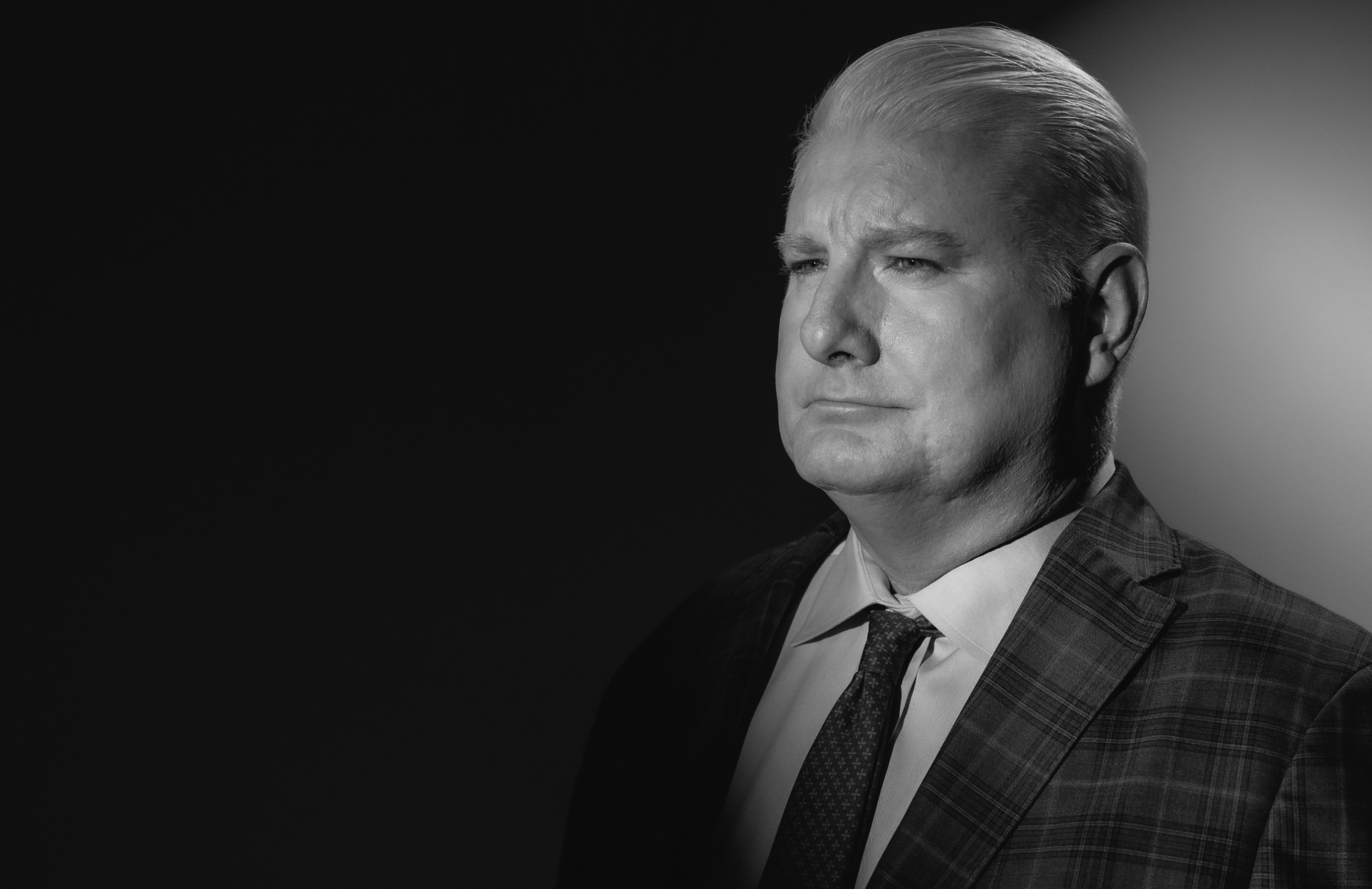

Moshe MaimonManaging Partner at Levy Konigsberg

Who takes on powerful entities that jeopardize public health?

Moshe Maimon,

that’s who.

Trial Lawyers Find the Truth in Pursuit of Justice

Moshe Maimon has built his reputation on taking complex personal injury cases others would not – cases other lawyers deemed too risky, too unusual, too impossible to win.

Still, he stood in courtrooms across the country representing children poisoned by their own water, women and families unknowingly exposed to asbestos, and families destroyed by the very institutions they once trusted.

In fact, he became so renowned for it that one day, a judge called him on it during a trial. He remembers the judge looking down at him and asking plainly: “Mr. Maimon, why is it that you handle all the oddball cases?”

“I told the judge, those [oddball] cases haven’t been done before, but they provide the opportunity to help someone who really needs the level of dedication, devotion, and excellence [we’re] going to bring,” Moshe recounts.

Though that experience happened decades ago, his casework has remained the same. Because now, as managing partner at contingency fee law firm Levy Konigsberg in New York City, he continues to stake his claim on these challenging cases, not only seeing justice served, but also futures safeguarded.

“Sometimes the deck is stacked against the little guy; the individual against the corporation; the single person against an institution; the citizen against the government,” says Moshe. “It was something that I felt a moral necessity: to represent those people who couldn’t represent themselves.”

With such a strong instinct to fight for the underdog, it makes sense that it started long before law school, long before he ever stepped foot in a courtroom as a trial lawyer. It was rooted in the example set by his father, a lawyer with a mission to serve those the system left behind.

Keeping the wheel of justice turning

“My dad was a lawyer, and later on in his career, he represented veterans who were disabled and unable to handle their own affairs,” Moshe explains. “I saw that and said, not only do I want to be a lawyer, but I really want to be a voice for those who don’t have one.”

Witnessing how the law could serve as a moral force, a way to advocate for those overlooked by systems, might motivate anyone. But for Moshe, it was confirmation that the law wouldn’t be just a career, but a calling. And, as a trial attorney working on contingency fee, he’d do it for no money down.

Because if you ask Moshe, his clients are the reason he wakes up every day and chooses such challenging work. It’s not for the recognition, not for the glory, and certainly not for the paycheck. It’s fulfilling a mutually beneficial agreement: to keep the wheel of justice turning.

“A special thing about our area of practice [contingency fee law] is that the interests of the lawyer and the client are completely aligned. A lawyer [is not interested in] spending unnecessary hours just to increase a bill,” Moshe notes. “Therefore the client understands that we are never going to do better for ourselves unless we do better for them.”

But that’s not to say being a trial lawyer doesn’t take work. Moshe would be the first person to tell you just how much work it demanded, and not to mention, how much a difference it made.

“When it comes to great trial lawyers, some are born and some are made. I think I was made,” Moshe quips. “I’m the second of four children, and my older brother was way smarter than I was. So I had to keep pace, learn how to argue, and understand how that was going to make me succeed.”

And Moshe would do more than keep pace at Levy Konigsberg, contributing to more than $3 billion won for its clients and pioneering representation for victims of asbestos exposure.

Searching for the Truth: Asbestos in Baby Powder

The average person has probably heard of asbestos in relation to housing or construction. But for Moshe, it was in a very unlikely place: talcum powder, otherwise known as baby powder.

Though, at the time, it wasn’t immediately that obvious. All Moshe knew was that his client, a potter, had been diagnosed with a type of incurable cancer only caused by asbestos: mesothelioma.

“We had a hard time figuring out where he was exposed to asbestos until I asked him about his work,” Moshe remembers. “He ran a pottery studio and used talc for his glazes.”

From there, Moshe did exactly what he believes all great trial lawyers do to make a case for justice: turn over every stone to find the truth. After researching talc and its origins, the pieces started fitting together. It wasn’t that asbestos was being added to talcum powder – the common misconception Moshe heard time and time again. As it turns out, asbestos was a naturally occurring environmental hazard.

“Talc is a mineral. It’s mined throughout the world. It’s one of the softest minerals around, and that’s why it’s ground really finely [into] a soft, powdery material,” Moshe explains. “But asbestos is also a mineral. And since minerals grow in the ground, they tend to grow together. Asbestos is just a contaminant of talc.”

That simple truth was the monumental turning point. After trying the potter’s case, Moshe won the country’s first mesothelioma verdict against a talc manufacturer. Unfortunately, asbestos contamination in talcum powder didn’t cease after that important verdict.

Brands Breaching Consumer Trust

“We started having clients come in where there was no other exposure except [the company’s] baby powder,” recalls Moshe. “We found that people who had heavy use or exposure to talcum baby powder when they were kids developed mesothelioma later on in life. We also found there was more ovarian cancer among women who heavily used talcum baby powder on a regular basis.”

These consistent and alarming instances drove Moshe and his team to seek answers in the pursuit of justice for those suffering from mesothelioma – an illness instigated by one of the country’s most trusted brands.

“When a mother or father chooses to use a product on their baby, they’re showing a tremendous amount of trust. It’s the way the product was marketed to them – that it was completely pure and safe,” says Moshe. “When we found asbestos in the baby powder, we said we have to represent these people because that trust was betrayed.”

But as it turned out, the issue wasn’t only the contamination – it was the cover-up. While reviewing due diligence documents from talc mining companies, Moshe discovered summaries of tests confirming asbestos contamination in its talc. Even worse, the testing was designed in a way that would avoid detection.

“We found that [the company’s] contamination testing was purposely insensitive so that results wouldn’t find the asbestos the company knew was there,” tells Moshe. “We always compare it to putting a few ping pong balls on a bathroom scale – [the scale] will say zero, even though the ping pong balls are there. You’ve got to get an atomic scale to measure it.”

This historic discovery put Levy Konigsberg in a league of its own as one of the few firms in the country to try multiple cases against the multinational healthcare corporation. In 2016, the company was found responsible in two separate cases involving their dangerous talcum powder products and ordered to pay $72 million and $55 million respectively.

Though the multinational healthcare company has refused to admit that talcum powder can cause fatal illnesses like mesothelioma and ovarian cancer, the corporation pulled its talc-based baby powder products off global shelves in 2023, according to Levy Konigsberg’s website.

“Sometimes the deck is stacked against the little guy; the individual against the corporation; the single person against an institution; the citizen against the government. It was something that I felt a moral necessity: to represent those people who couldn’t represent themselves.”

Moshe Maimon

Managing Partner at Levy Konigsberg

“Sometimes the deck is stacked against the little guy; the individual against the corporation; the single person against an institution; the citizen against the government. It was something that I felt a moral necessity: to represent those people who couldn’t represent themselves.”

Moshe Maimon

Managing Partner at Levy Konigsberg

Seeking justice for Flint, Michigan

There’s an unfortunate truth to being a trial lawyer, and that is: by the time they learn about a person and/or industry’s negligence, the damage has already been done. It was true in the case of the asbestos-laden baby powder, just as it was true about Moshe’s next sprint of landmark cases: the contaminated water in Flint, Michigan.

As it turns out, thousands of Flint residents – many of them children – had been exposed to toxic levels of lead through their drinking water for over a decade. As the crisis unfolded across national headlines, it was more than just news for Moshe. It was a call to action.

“[The firm said], if we’re not going to get involved, then we have no business doing what we do,” Moshe remembers.

The Flint water crisis began in 2014 when officials switched the city’s water supply from Lake Huron to Flint River without properly treating it – all in the hopes of saving money. The result: lead contamination, exposing residents, particularly children, to its dangerous effects.

Despite early complaints of health issues like rashes and hair loss, state officials claimed the water was safe. It wasn’t until 2015, after pediatricians found elevated lead levels in children’s blood, that the state publicly acknowledged the crisis.

“Our firm has worked on the Flint water crisis, not only representing thousands of children who were lead poisoned but also taking a leadership role in the litigation and achieving an unprecedented settlement on behalf of the citizens of Flint,” says Moshe.

According to Levy Konigsberg’s website, a $626 million settlement was approved in 2021 for tens of thousands of Flint residents harmed by the city’s contaminated water supply. It was the largest civil settlement in Michigan’s history, with the majority of funds allocated to children exposed to lead during the crisis.

Levy Konigsberg played a leading role in the litigation, where Moshe’s partner Corey Stern served as lead counsel for the plaintiffs, representing more than 2,600 children. The firm’s work in both state and federal proceedings helped secure the $600 million settlement.

“The Flint litigation has empowered its citizens – not only on a local level, but on a national level – to call out their government officials,” states Moshe. “And the impact has been really important, [where now] the way water is tested and regulated around the country has been changed by the litigation.”

Moreover, after 10 years of living with unsafe drinking water, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has finally declared that Flint’s water is safe to drink, thanks to those new regulations. But according to Moshe, the fight is far from over.

“Together with one of my partners, I’m scheduled to try the lawsuit against the United States Environmental Protection Agency this coming January [2026],” states Moshe.

Trust, Integrity, and the Esquire Advantage

At Levy Konigsberg, pursuing justice at this scale requires more than moral clarity – it requires resources. And since the contingency fee model is often seen as “risky” by traditional banks, Moshe needed a financial partner who acknowledged and understood the unique needs of his business.

“When you deal in high-impact litigation against governments, against corporations, against institutions that are going to fight all the way, there aren’t regular accounts receivable like in other businesses,” Moshe explains.

Because contingency fee firms only get paid if they win a case, that means cash flow can be inconsistent, affecting every part of the business – from keeping the lights on to paying office staff a livable wage.

Fortunately with an institution like Esquire Bank – a business built by attorneys for trial lawyers – firms like Levy Konigsberg can access the financial footing they need to continue pursuing justice while keeping their business running.

“One thing that’s special about Esquire is that they get it – they understand the finances of a law firm like ours,” Moshe says. “Esquire Bank helps us bridge the gap between when the expenses are incurred and when the recovery is made.”